The Link Between Mold Illness and Lyme Disease

Nutrition, sleep, exercise, and stress management are essential elements of a comprehensive Lyme disease treatment protocol. However, have you ever stopped to think about the impact of your living environment on your overall health and recovery process?

Recent statistics indicate that the average adult living in the Western world spends a whopping 80 to 90 percent of his or her time indoors.1 People with chronic illnesses may spend even more time indoors due to energy and mobility restrictions. Ideally, all of our indoor time should be spent in safe, clean environments. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. A surprising number of residential buildings, schools, and workplaces are contaminated by an environmental toxin that can hinder healthy immune function and complicate the Lyme treatment process – mold. Read on to learn about the relationship between toxic mold exposure and Lyme disease, and why treating mold-induced illness is essential for Lyme healing.

What’s the Big Deal with Indoor Mold Growth?

If you’ve ever lived or worked in a building with a leaky basement, visible mold growth, or a pervasive musty odor, you may have experienced exposure to toxic mold. Mold grows both indoors and outdoors; however, the types of mold that grow indoors are the ones that tend to be harmful to our health.

According to the World Health Organization, up to fifty percent of the buildings in North America are water damaged and potential sources of indoor toxic mold exposure.2 Molds such as Aspergillus and Stachybotrys chartarum like to take up residence in damp environments filled with porous materials, including wood, particleboard, and drywall. Constant high humidity, such as is found in most bathrooms or a small leak into a basement, is all it takes to create an environment hospitable to indoor toxic mold growth. Most people have lived, worked, or otherwise spent time in a building where visible mold was growing on the grout in the bathroom, or an unpleasant musty odor filled the air. However, these signs of mold growth are not innocuous, and definitely not something that should be ignored, particularly in those dealing with Lyme disease and other tick-borne infections.

Mold Exposure and Lyme Disease: A Dangerous Combination

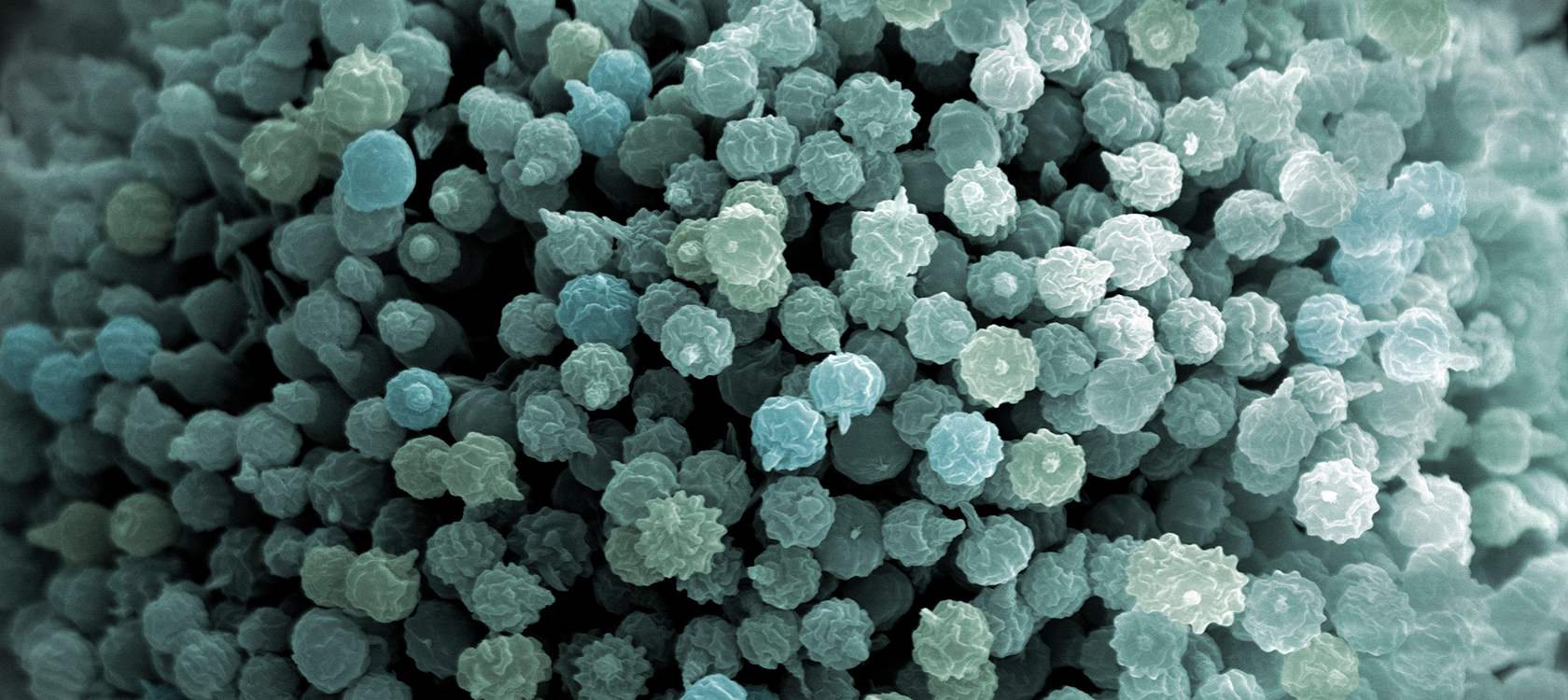

The real problem begins once mold “settles in” to its newfound home and proceeds to release mycotoxins, secondary metabolites with an array of harmful effects. Mycotoxins can be inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed via skin contact in mold-infested buildings; over time, this chronic exposure can contribute to a significant body burden of mycotoxins and an aberrant immune response. At CCFM, we routinely test for markers of this abnormal immune response to identify people with a potential mold-induced illness.

Mycotoxins suppress the immune system and are thus particularly harmful to individuals with Lyme disease and other tick-borne infections. Chronic mycotoxin exposure reduces the body's ability to fight infection and may reduce the efficacy of antimicrobial treatments.

Mold exposure also provokes a robust inflammatory response that may worsen Lyme-related inflammation.3 There are many ways to reduce mold-induced inflammation using functional medicine; more on that shortly!

Symptoms of Toxic Mold Exposure

While toxic mold exposure can cause a wide variety of symptoms, some of the most common effects include:

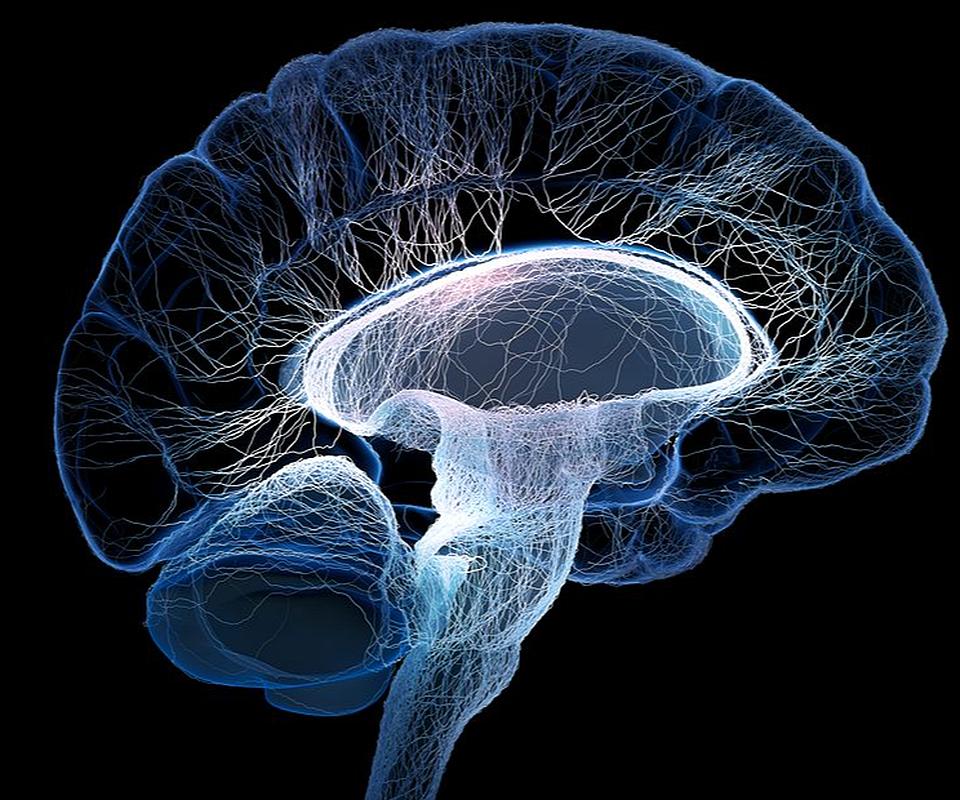

- Cognitive impairment or “brain fog, “ with difficulty thinking, concentrating, or with memory

- Impaired neuronal plasticity; impaired neuronal plasticity adversely affects everything from your ability to learn and retain new information to overall cognitive function4

- Mood swings

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Rapid weight loss or weight gain

- Chronic fatigue

- Respiratory issues

- Chronic sinusitis

- Headaches

Testing for Mold-Induced Illness

There are a variety of tests that can be helpful to determine if mold is a possible trigger or problem for you. While none are absolutely specific for mold, when taken together these tests can be very helpful in confirming the diagnosis. We routinely check labs such as HLA typing (to assess genetic predisposition for difficulty clearing mold toxins), MSH, MMP-9, TGFBeta-1, and C4a levels to start. We also frequently ask patients to complete a Visual Contrast Sensitivity (VCS) test online. Your ability to differentiate contrast can help us understand if you are struggling with mold related brain inflammation. We also look at mold and yeast markers on stool, blood, and urine organic acid markers. In some cases we will also check urine mycotoxin testing, but in our experience these tests are limited in their clinical utility and thus we use them infrequently.

Our Treatment Approach to Mold Illness

At CCFM, we take a multifaceted approach to the treatment of mold-induced illness.

- First, if you are sensitive to mold and are being exposed, you must remove yourself from the mold-contaminated environment. Continued exposure to mold makes it very challenging, if not impossible, to make progress with treatment. If you suspect that your home is contaminated with indoor mold, we will likely ask you to collect a dust sample and perform an Environmental Relative Moldiness Index (ERMI) or HERTSMI-2 test with Mycometrics laboratory. We can also connect you with an indoor environmental professional who can guide you through the environmental mold testing process.

- Next, we begin by incorporating binders into patients’ treatment protocols. Binders are natural substances that “mop up” toxins, including mycotoxins, in the gastrointestinal tract. This prevents the mycotoxins from being continuously recirculated between the liver, blood, and gut. Common binders include activated charcoal, bentonite clay, and chitosan. There are also prescription options such as Welchol and cholestyramine

- It is also essential to begin calming mold-induced inflammation. There are many ways to approach this through dietary changes, supplements, and lifestyle practices, such as brain retraining.

- Other aspects of health that may need to be addressed in the mold-affected patient include the gut microbiota and hormonal balance. Optimal gut, liver, and gallbladder function are critical to be able to eliminate mold toxins. Research also shows that mycotoxins knock down numbers of beneficial gut bacteria and increase opportunistic and pathogenic microbes, creating an unhealthy gut ecosystem. Probiotics and botanical antimicrobials can help restore a healthy balance to the gut microbiome.

Hormones can also be thrown off-kilter by chronic mold exposure. Treatments designed to support healthy hormone levels, such as dietary changes and adaptogens, can help tremendously in rebalancing hormones that have been impacted by toxic mold exposure.

It is important to understand that mold illness and Lyme disease can mimic each other, and there is significant overlap in the symptoms of these distinct illnesses. Furthermore, in many patients, both can be present as one can unmask or trigger the other. It is critical for optimal recovery that you are evaluated for both tick borne infections and mold toxicity, and treated appropriately. If you’ve been exposed to toxic mold in your environment, identifying and treating this exposure may be an essential component of your Lyme disease recovery process. At CCFM, we can help you determine whether mold exposure may be impacting your recovery and guide you through the process of treating mold-induced illness.

References

- Al horr Y, et al. Impact of indoor environmental quality on occupant well-being and comfort: A review of the literature. Int J Sustain Built Environ. 2016; 5(1): 1-11.

- Anderson B, et al. Associations between fungal species and water-damaged building materials. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011; 77(12): 4180-4188.

- Hope J. A Review of the mechanism of injury and treatment approaches for illness resulting from exposure to water-damaged buildings, mold, and mycotoxins. Sci World J. 2013; 2013: 767482.

- Scafuri B, et al. Binding of mycotoxins to proteins involved in neuronal plasticity: a combined in silico/wet investigation. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 15156.